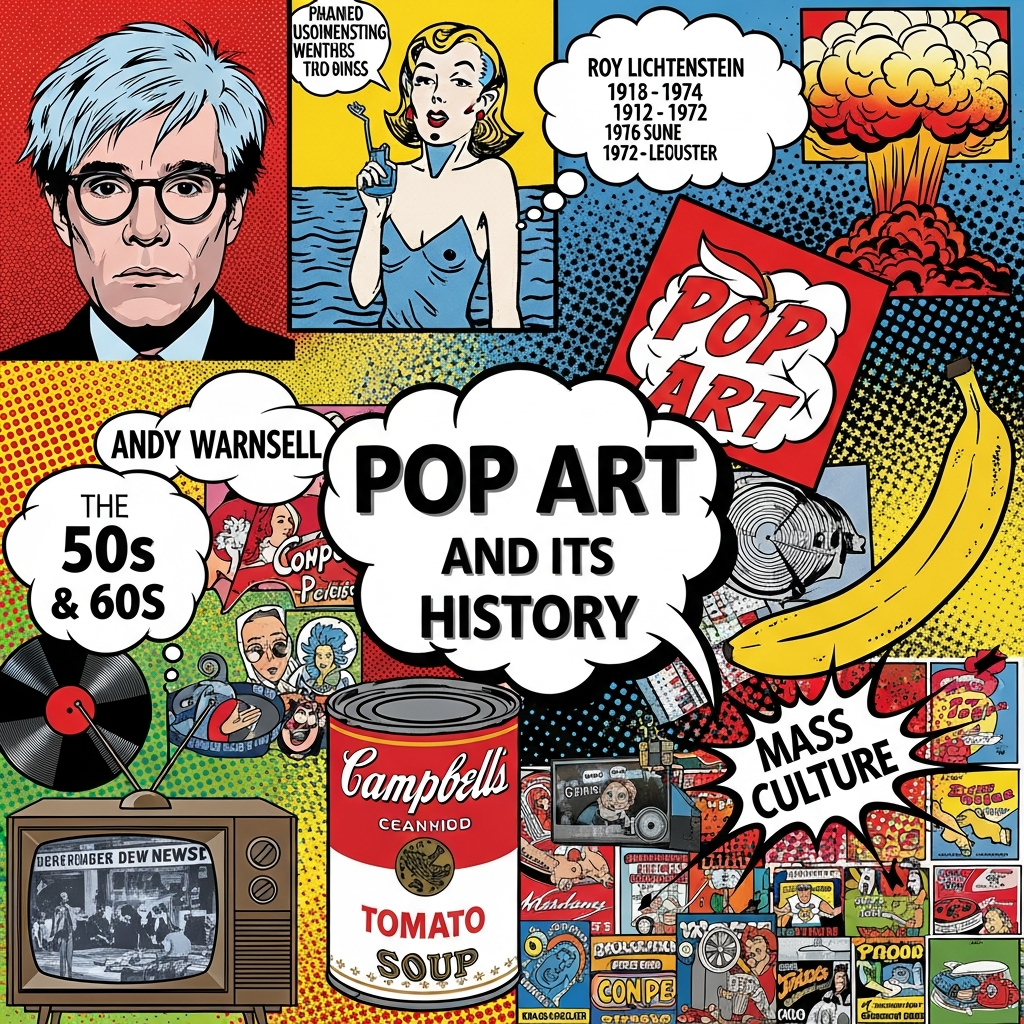

Welcome to a world where soup cans became masterpieces and comic book panels transformed into high-brow commentary. If you’re looking to dive deep into a vibrant movement that fundamentally changed how we view art, consumption, and celebrity, then you’ve come to the right place. Understanding Pop Art and Its History is key to grasping modern aesthetics, because this movement didn’t just decorate museums—it invaded our living rooms, our closets, and our entire cultural landscape.

This revolutionary style took root in the mid-1950s and reached its peak in the 1960s, quickly becoming one of the most recognizable and enduring art forms of the 20th century. Pop Art and Its History is a narrative about challenging the elite and embracing the popular. It was an intentional departure from the introspective and often abstract work that dominated the art world previously, choosing instead to celebrate the mundane, mass-produced imagery of everyday life. The sheer vitality and rebellious nature of Pop Art and Its History ensure that its lessons remain relevant even today.

It is impossible to discuss the foundation of modern visual culture without thoroughly examining Pop Art and Its History, which saw artists turn commercial objects into fine art subjects. By focusing on popular media, advertising, and celebrity, this movement effectively blurred the lines between high culture and low culture. For the average person, it offered a much-needed bridge into the intimidating world of art, and that accessibility is central to the entire narrative of Pop Art and Its History. The story is fascinating, and its impact is truly monumental.

What is Pop Art? A Direct Challenge to the Old Guard

Pop Art is an art movement that emerged in Britain and America during the mid-to-late 1950s, using imagery from popular and commercial culture as its primary subject matter. The movement was a reaction against the seriousness and perceived elitism of Abstract Expressionism, instead favoring accessible, everyday objects and mass-produced media.

Pop Art, short for “Popular Art,” challenged the distinction between ‘fine art’ and ‘low culture.’ It was a complete philosophical shift that celebrated mass consumerism, commercial branding, and media ubiquity. The artists were not just painting a picture; they were commenting on the rapidly expanding post-war world defined by television, print advertising, and the cult of celebrity. This deliberate choice of subject matter is the single most defining factor of Pop Art and Its History.

The movement is best defined by several key characteristics that were radically new at the time.

| Characteristic | Description | Key Examples |

| :— | :— | :— |

| Common Imagery | Objects and figures drawn from mass media, advertising, and everyday life. | Campbell’s Soup Cans, Comic Strips, Coca-Cola bottles. |

| Mechanical Techniques | Use of industrial and commercial printing processes (like silkscreening) to mimic mass production. | Warhol’s serial images, Lichtenstein’s Ben-Day dots. |

| Bold, Hard Edges | Adoption of graphic-design aesthetics with clear lines and often primary colors. | Clean lines found in advertisements and comic books. |

| Irony & Parody | A subtle or overt commentary on the superficiality of consumer culture and the nature of celebrity. | Lichtenstein’s parodic paintings of melodrama. |

This intentional shift from the personal, emotional chaos of Abstract Expressionism to the impersonal, cool detachment of commercial design is one of the most important chapters in Pop Art and Its History. It was a move that simultaneously shocked and delighted the viewing public, making art relatable in a way it hadn’t been for decades.

The Core Philosophy Behind the Movement

The philosophy driving Pop Art and Its History was fundamentally democratic. Abstract Expressionists viewed art as a profound, unique expression of the inner self, a serious pursuit reserved for the culturally knowledgeable. Pop artists, conversely, believed that culture was culture, regardless of its source. They leveled the playing field by asserting that a billboard advertisement had as much artistic potential as a landscape painting. This idea that art could be, and should be, instantly recognizable and easily understood was revolutionary.

This embrace of the commercial was not always a celebration; often, it was an attempt to critically engage with the overwhelming visual environment of post-war capitalism. Artists like Andy Warhol used repetition and serialization to mimic the conveyor belt of the factory and the endless loop of mass media. By presenting a row of identical Marilyn Diptychs or Brillo Boxes, he forced the viewer to confront the banality and overwhelming saturation of images in their daily lives. Analyzing these motivations is crucial to fully appreciating Pop Art and Its History.

The core belief was that the subject matter of art should be drawn from the public domain. It was a visual language everyone already spoke—the language of television jingles, product labels, and movie posters. This accessibility is what gave Pop Art and Its History its immediate and global appeal. It was a rejection of the academic structure of art that had long been inaccessible to the working and middle classes.

Defining Characteristics of the Pop Art Style

The look of Pop Art is unmistakable, relying heavily on visual cues borrowed directly from graphic design and industrial processes. Artists adopted commercial techniques to give their work an anonymous, mass-produced quality, effectively taking the artist’s ‘hand’ out of the equation. This was a direct provocation against the Abstract Expressionist focus on the brushstroke as a unique, personal signature.

One of the most instantly recognizable elements of Pop Art and Its History is the use of the Ben-Day dot technique, famously employed by Roy Lichtenstein. These small, closely spaced dots, typically used for coloring in comic books and cheaper printing, became a signature stylistic choice. Lichtenstein magnified these dots to monumental scale, turning a low-fidelity printing technique into a high-art statement. This use of industrial aesthetics is central to understanding the visual mechanics of Pop Art.

Furthermore, the palette was typically vibrant and highly saturated, eschewing the muted or complex tones of earlier movements in favor of the shocking primary colors found in advertising and product packaging. Think of the bright reds, yellows, and blues that jump out at you from an old billboard. This aesthetic choice helped the work convey an immediate, almost jarring impact, perfectly matching the frenetic energy of the consumer society it depicted. The marriage of common imagery with this specific, bold aesthetic is the bedrock of Pop Art and Its History.

The Dual Birthplace: Pop Art and Its History in the UK and US

Tracing the origins of Pop Art and Its History leads us to two distinct geographical locations: London, England, and New York, USA, each developing the movement with slightly different motivations and timing. The Independent Group in Britain began exploring these themes earlier, while American artists, driven by a more intense consumer culture, ultimately propelled the movement to global fame. This dual genesis explains much of the subtle differences we see in the earliest works of Pop Art and Its History.

The British movement, starting in the mid-1950s, was often more academic and analytical, reflecting on American popular culture from a critical distance. They were reacting to the influx of American mass media—Hollywood films, jazz music, and glossy magazines—as something exotic and powerful. Conversely, the American movement, which gained momentum in the late 1950s, was a more direct, immediate immersion in and acceptance of the consumerist environment. Both played equally critical roles in shaping Pop Art and Its History.

Understanding this transatlantic conversation is crucial to fully grasping the movement’s scope. It was a cultural feedback loop: British artists analyzed American culture, and then American artists took that analytical framework and applied it with a powerful, native force. The result was a movement that felt both globally relevant and intensely local, showcasing a fascinating interplay in Pop Art and Its History.

The Independent Group: British Pioneers

The true spark for Pop Art and Its History occurred in London around 1952 with the formation of the Independent Group (IG), a collective of artists, architects, and writers who met at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA). Their discussions centered on the implications of mass culture, technology, and advertising. They were the first to take the subject of American comic books, science fiction, and car design seriously as material worthy of artistic consideration.

Two names stand out from this period: Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton. Paolozzi, through his 1947 collage series Bunk!, which featured imagery torn from American magazines, is often credited with one of the earliest precursors to Pop Art. His work already demonstrated the technique of fragmenting and juxtaposing mass-media imagery, laying the conceptual groundwork for the visual style that would define Pop Art and Its History.

Richard Hamilton is frequently cited for providing the first definitive definition and image of the movement. His 1956 collage, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, is widely considered the inaugural artwork of Pop Art. The piece is a dense assemblage of images clipped from magazines—a bodybuilder, a vacuum cleaner hose, a canned ham—all satirically illustrating the material desires of the post-war suburban dream. Hamilton also famously enumerated the characteristics of Pop Art, defining it as “Popular, Transient, Expendable, Low cost, Mass produced, Young, Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, and Big Business.” This analytical approach is what distinguishes the British contribution to Pop Art and Its History.

The American Powerhouse: Warhol and Lichtenstein’s Revolution

While the British laid the intellectual foundation, the Americans, led by figures like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and James Rosenquist, gave Pop Art and Its History its electrifying energy and global celebrity. America in the late 1950s and early 1960s was the epicenter of the post-war economic boom, meaning consumer culture was not an academic subject, but an overwhelming reality. American Pop Art reflected this immediacy and scale.

American artists embraced the cool, impersonal aesthetic of commercial production. Unlike the more conceptual collages of the British artists, Americans utilized the actual scale, technique, and repetition of mass media. Lichtenstein’s massive canvases of single comic book panels, complete with Ben-Day dots, turned cheap, disposable narrative into museum-worthy scale. This transformation of scale is a hallmark of Pop Art and Its History in the United States.

Andy Warhol, of course, became the ultimate figurehead. His use of silkscreen printing to churn out identical images of cultural icons (Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley) and commercial goods (Campbell’s Soup Cans, Coca-Cola bottles) was a game-changer. Warhol’s factory-like approach—ironically titled “The Factory”—epitomized the movement’s philosophy: if society is mass-producing culture, the artist should mass-produce art. His profound impact on celebrity culture and mass media is an inseparable part of Pop Art and Its History. The power of this movement in the US stemmed from its deep, unfiltered engagement with the country’s unique brand of consumerism.

The Iconic Figures Who Shaped Pop Art and Its History

Any deep dive into Pop Art and Its History must focus on the giants who defined its visual language. These artists weren’t merely painting pictures; they were forging a new relationship between art, commerce, and the public. Each artist brought a distinct perspective, yet all were united by a commitment to the imagery of popular culture. Their collective body of work is what cemented the legacy of Pop Art and Its History as a true cultural phenomenon.

The sheer volume and immediate recognizability of the works created by these masters ensured that Pop Art became a household name. These figures managed to elevate what was considered ‘trash culture’ into the highest realm of fine art, a remarkable feat that continues to inspire artists today.

Andy Warhol: The Commercial King

Andy Warhol is, without a doubt, the most recognizable name when discussing Pop Art and Its History. His career was a masterful fusion of art, celebrity, and commercialism that fundamentally changed the definition of an artist in the modern era. Warhol didn’t just paint popular culture; he became popular culture, making his life and process as much a part of the movement as his finished pieces.

Warhol’s method relied heavily on the silkscreen printing technique. This mechanical process allowed him to reproduce images rapidly, playing directly into the theme of mass production and celebrity ubiquity. His iconic works, such as the Marilyn Diptych and his various celebrity portraits, used bold, garish colors to transform a photograph into a reproducible icon, often exploring the dark side of fame and the dehumanization that comes with being a mass-market commodity. This serialization is key to the entire narrative of Pop Art and Its History.

He was a prolific artist, producing thousands of images that ranged from the instantly recognizable to the more provocative. His early works, like the 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962), are a perfect example of his philosophy. By displaying a common grocery item in an art gallery, Warhol forced viewers to question the boundary between the supermarket and the museum. This elevation of the mundane object is perhaps the most lasting contribution Warhol made to Pop Art and Its History.

Roy Lichtenstein: The Comic Book Philosopher

Roy Lichtenstein gave Pop Art and Its History its signature graphic style, transforming the disposable medium of the comic strip into meticulously crafted, large-scale paintings. His work is a brilliant blend of mechanical appearance and hand-painted precision. Lichtenstein didn’t just copy comic panels; he reframed them, dramatically altering their scale, color, and context to create a new form of cultural commentary.

Lichtenstein’s subject matter was usually drawn from romance comics or war stories, often focusing on dramatic close-ups of faces or action. He would meticulously recreate the cheap printing effects, most famously the Ben-Day dots, by stenciling or painting them onto the canvas. This process was extremely laborious—a deliberate counterpoint to the rapid, inexpensive process he was imitating. The famous Whaam! (1963) and Drowning Girl (1963) are masterpieces of this transformation, injecting emotional melodrama with cool, aesthetic detachment.

His contribution to Pop Art and Its History was the philosophical exploration of the image. By isolating a single frame, he stripped the narrative context away, forcing the viewer to analyze the visual tropes and clichés of mass media. His work questions the nature of communication and the way emotions are simplified and commercialized in the printed world. This intellectual rigor beneath the fun, colorful surface is what makes Lichtenstein a crucial figure in Pop Art and Its History.

Other Essential Pop Art Contributors

While Warhol and Lichtenstein dominate the spotlight, a thorough understanding of Pop Art and Its History requires acknowledging the contributions of several other pioneering artists who pushed the boundaries of the movement:

- Claes Oldenburg: Known for his massive, soft sculptures of everyday objects, Oldenburg took the Pop Art interest in the commodity and gave it a physical, often humorous, presence. His sculptures, like a giant clothespin or an enormous rubber stamp, challenged the permanence and traditional scale of fine art. His work is essential to the conceptual history of Pop Art and Its History, proving that art could be fun, floppy, and ridiculously oversized.

Robert Indiana: Indiana’s work elevated the power of language and simple graphic design. His famous LOVE* sculpture, originally a painting, used stackable, hard-edged lettering and a simple, limited color palette to create an image that became instantly synonymous with the late 1960s. This transformation of a simple four-letter word into a colossal, universal icon highlights the movement’s ability to turn graphic simplicity into powerful, public art. The sheer graphic authority of his pieces remains a core element in the visual vocabulary of Pop Art and Its History.

James Rosenquist: Having worked as a commercial billboard painter, Rosenquist brought a unique perspective and scale to his fine art. His enormous, fragmented collages of advertising imagery, such as F-111* (1965), force the viewer to read consumer products and military technology in the same visual breath. His work reflects the chaotic, non-linear way mass media bombards the modern eye, offering a complex, kaleidoscopic view of Pop Art and Its History.

The Enduring Impact of Pop Art on Modern Culture and Design

The influence of Pop Art and Its History did not stop when the 1960s ended; it merely transformed and integrated itself into the global visual vocabulary. The movement acted as a massive cultural catalyst, fundamentally changing the relationship between art, commerce, and the everyday object. Today, we see its legacy everywhere, from the graphics on our clothes to the design of our digital interfaces. The tenets established by Pop Art and Its History have become foundational to nearly all contemporary creative industries.

The movement’s most significant impact was its permission to mix categories. By demonstrating that high quality art could borrow freely from commercial sources, Pop Art liberated designers, musicians, and filmmakers from traditional hierarchies. This cross-pollination of disciplines is a defining trait of the modern creative economy, and it all traces back to the initial, shocking statements made during the height of Pop Art and Its History.

From Fine Art to Fashion and Advertising

The feedback loop between Pop Art and Its History and the commercial world became a defining characteristic of modern design. Artists like Warhol started as commercial illustrators, and their fine art was quickly re-absorbed into advertising. The boldness, clarity, and shock value inherent in Pop Art were instantly appealing to marketers looking to cut through the noise.

In fashion, the influence was immediate and visceral. The graphic simplicity, bold blocks of color, and appropriation of motifs from everyday items directly inspired designers in the 1960s and beyond. Think of the geometric dresses, the mod aesthetic, and the widespread use of plastic and vinyl, which echoed the industrial materials celebrated by Pop artists. Even in contemporary fashion, designers frequently reference the color schemes and graphic authority of Pop Art and Its History.

In the world of advertising and graphic design, Pop Art codified the look of the modern, impactful brand. The use of simplified, clean typography, the focus on brand logos as cultural icons, and the use of shocking color palettes all owe a debt to the movement. Every time a designer uses a bright, saturated color to make a product “pop” off the screen, they are unknowingly drawing from the visual lexicon established by Pop Art and Its History. The art became the advertisement, and the advertisement became art—a cycle of influence that continues unabated.

The Democratization of Art

Perhaps the most profound and lasting influence of Pop Art and Its History is the democratization of art itself. Before this movement, much of the public felt alienated from contemporary art, finding Abstract Expressionism too esoteric and elitist. Pop Art fixed this problem by providing a familiar, welcoming entryway.

By using images of Marilyn Monroe, Mickey Mouse, and household products, Pop Art made the artwork instantly legible to anyone, regardless of their artistic education. There was no need to read a complex manifesto or understand decades of art theory to appreciate a painting of a can of soup. You knew the soup. You knew the celebrity. This accessibility fostered a new public appreciation for modern art. The popularity of the pieces created by artists who defined Pop Art and Its History brought a massive influx of new people to galleries and museums.

Furthermore, the techniques used—especially silkscreen printing—demystified the production process. The idea that an artist could produce a series of nearly identical works, or that an artwork could be based on a commercial photograph, challenged the sacred idea of the single, unique, handcrafted masterpiece. This challenge to the ‘aura’ of fine art made collecting more accessible and broadened the base of people who felt they could participate in culture. This legacy of accessibility is a vital part of Pop Art and Its History.

The Current Market and Timeless Appeal of Pop Art and Its History

The enduring relevance of Pop Art and Its History is nowhere more evident than in the contemporary art market. Decades after its inception, Pop Art remains one of the most bankable and desirable categories for collectors worldwide. Its continued high performance at auctions and its persistent presence in major museum exhibitions prove that this is not a flash-in-the-pan trend, but a cornerstone of art history.

While the global art market saw some contraction in certain years (for example, the global art market recorded approximately \$57.5 billion in sales in 2024, a 12% decline by value compared to the previous year), the segment of high-value, iconic works from Pop Art and Its History often demonstrates significant resilience. Works by the movement’s titans continue to set staggering records, solidifying their status as blue-chip investments.

The themes central to Pop Art and Its History—consumerism, celebrity, media saturation—are arguably more relevant today than they were in the 1960s. We live in an age of pervasive digital media, social celebrity, and constant visual noise. Pop Art’s visual vocabulary provides a perfect lens through which to understand our hyper-commercialized world, ensuring its continued intellectual and commercial appeal.

Auction Records and Collector Trends

The value of the masters who defined Pop Art and Its History is consistently proven at auction houses across the globe. Warhol and Lichtenstein are perennial top-sellers, commanding prices that place them among the most successful artists of the 20th century. For example, works featuring familiar icons from the Pop Art canon often see fierce bidding wars.

The trend for collectors is not just about owning a piece of art; it is about owning a piece of cultural commentary. The clean aesthetics and recognizable imagery of Pop Art and Its History make it highly adaptable to modern interior design, further boosting its broad market appeal. Collectors are often drawn to the bright, unapologetic optimism and visual clarity of Pop Art, which acts as a vibrant counterpoint to contemporary anxieties. This commercial success is a testament to the fact that the vision of Pop Art and Its History still resonates powerfully with modern sensibilities.

Moreover, a recent trend in the broader art market suggests an increasing interest in “retro-inspired art” that captures the charm of the past and reimagines it for the modern world. Since Pop Art and Its History is the ultimate form of retro-inspired, visually charming art, it continues to influence current purchasing decisions. The enduring power of the movement’s most famous motifs—like the Campbell’s soup can or the Ben-Day dots—acts as a consistent, powerful market driver.

The Ongoing Influence on Contemporary Artists

Contemporary artists across various disciplines continue to draw heavily from the principles of Pop Art and Its History. The idea of appropriation—taking existing imagery and repurposing it—which was pioneered by Pop artists, is now a fundamental tool in the modern artist’s toolkit. From street art to digital collages, the spirit of taking a common image and recontextualizing it as art is a direct descendant of the Pop movement.

The influence of Pop Art and Its History is evident in the work of many modern artists who use branding, internet memes, and digital imagery to comment on modern culture. They are essentially updating the Pop Art subject matter for the 21st century. Where Warhol used the mass production of the silkscreen, today’s artists use the infinite reproducibility of the digital file to make their point. They continue the dialogue about fame, consumerism, and reproduction that began with Pop Art and Its History.

Ultimately, the most important lesson contemporary artists take from Pop Art and Its History is permission to be brave, playful, and relevant. The movement proved that art does not need to be serious to be profound, and that the most powerful messages are often found in the most common places. This legacy of accessibility, commercial critique, and formal innovation ensures that Pop Art and Its History will remain a vital source of inspiration for generations to come.

—

Conclusion

We have explored the revolutionary journey of Pop Art and Its History, tracing its origins from the intellectual circles of the British Independent Group to the explosive, commercial energy of the American art scene. This movement successfully tore down the walls separating high art from popular culture, introducing a visual vocabulary that was bold, accessible, and profoundly relevant to the post-war consumer age. By embracing the imagery of advertising, celebrity, and mass production, artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein didn’t just create art; they redefined its very purpose and audience.

The genius of Pop Art and Its History lies in its ability to be simultaneously simple and complex. On the surface, it is playful, colorful, and fun; underneath, it offers a sophisticated critique of modern society’s obsession with material goods and transient fame. Its adoption of mechanical techniques and its focus on repetition mirrored the mechanized nature of modern life, giving the movement a cool, objective distance that was a welcome change from previous artistic eras.

Today, the principles and aesthetics of Pop Art and Its History continue to dominate design, fashion, and marketing, making it one of the most culturally influential movements of the last century. Its market performance remains strong, confirming its status as a timeless and essential category in the art world. For anyone seeking to understand the visual bedrock of the modern era, a deep appreciation of Pop Art and Its History is absolutely indispensable.

—

FAQ (Pertanyaan yang Sering Diajukan)

What is the primary subject matter of Pop Art?

The primary subject matter of Pop Art is imagery drawn from popular and commercial culture. This includes everyday objects like soup cans, Coca-Cola bottles, and household appliances, as well as mass media sources like comic strips, advertisements, and celebrity photographs. The goal was to elevate these mundane, mass-produced items to the level of fine art, reflecting on the consumer culture of the mid-20th century.

Where and when did Pop Art begin?

Pop Art emerged concurrently in two main locations: The United Kingdom and The United States. In the UK, it began around the mid-1950s with the Independent Group in London. In the US, it gained significant momentum in the late 1950s and peaked in the 1960s with iconic artists working in New York.

Who are the most famous artists associated with Pop Art?

The most famous artists associated with Pop Art are:

- Andy Warhol (known for Campbell’s Soup Cans, Marilyn Monroe silkscreens).

- Roy Lichtenstein (known for large-scale paintings based on comic strips and Ben-Day dots).

- Claes Oldenburg (known for giant, soft sculptures of everyday objects).

Richard Hamilton (a British pioneer known for the seminal collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?*).

What techniques did Pop Artists commonly use?

Pop Artists often employed commercial and industrial techniques to achieve an impersonal, mass-produced look, distinguishing their work from the expressive brushstrokes of Abstract Expressionism. The most common techniques were:

- Silkscreen Printing (especially used by Andy Warhol for repetition and speed).

- Ben-Day Dots (used by Roy Lichtenstein to mimic cheap printing processes).

- Hard-Edge Painting (using sharp lines and clear color blocks borrowed from graphic design).

How did Pop Art change the art world?

Pop Art revolutionized the art world by:

- Challenging the Definition of Art: It blurred the line between “high” and “low” culture.

- Democratizing Art: It made art accessible and understandable to the mass public by using familiar imagery.

- Introducing New Techniques: It validated the use of mechanical, commercial processes in fine art production.

- Shifting Focus: It moved the focus from the internal, emotional life of the artist to the external, visual world of mass media and consumption.