Understanding Depth of Field in Photography

Understanding Depth of Field in Photography is one of the most fundamental skills any visual artist using a camera can master, and it acts as a powerful compositional tool. Simply put, Depth of Field (often abbreviated as DoF) is the range of distance in a scene that appears acceptably sharp, extending in front of and behind your exact point of focus. This distance, often referred to as the focus range, determines how much of your photograph, from the closest element to the farthest, is rendered clearly. Mastering the nuances of Understanding Depth of Field in Photography allows you to guide the viewer’s eye, isolate subjects with striking clarity, or ensure every element from foreground to background is pin-sharp. This complete guide on Understanding Depth of Field in Photography will meticulously break down the science and art behind this essential concept, ensuring you have the knowledge to control focus creatively in every shot.

What Exactly is Depth of Field (DoF)?

The concept of Depth of Field is often misunderstood as simply the area that is “in focus,” but the reality is slightly more complex. An image truly has only one single plane of perfect focus. This focus plane is the exact distance from the camera where the light rays converge perfectly. However, due to the limits of human visual perception, there is a zone immediately in front of and behind that perfect focal plane where subjects still appear sharp. This entire zone is the Depth of Field.

For Featured Snippet Optimization (Direct Answer):

Depth of Field (DoF) is the distance range within a photograph that appears acceptably sharp. It is primarily controlled by three interdependent factors, often called the “DoF Triangle,” which photographers manipulate for creative effect:

| Factor | Effect on Depth of Field | Typical Creative Use |

| :— | :— | :— |

| Aperture | Smaller f-number (e.g., f/1.8) = Shallower DoF | Portraiture, isolating a subject. |

| Focal Length | Longer (e.g., 200mm) = Shallower DoF | Wildlife, sports photography. |

| Focus Distance | Closer focus distance = Shallower DoF | Macro photography, close-up details. |

This subtle zone of acceptable sharpness is crucial for Understanding Depth of Field in Photography. For most practical purposes, approximately one-third of the total DoF lies in front of the exact focus point, and two-thirds lies behind it. This non-symmetrical distribution is a key element in Understanding Depth of Field in Photography, particularly when trying to maximize the sharpness in a landscape photograph. For instance, if you focus on a point 10 feet away, roughly 3.3 feet of sharpness will extend toward the camera, and 6.6 feet will extend away from it, although this ratio shifts depending on the focus distance and lens being used.

The Science Behind ‘Acceptable Sharpness’

To truly grasp Understanding Depth of Field in Photography, one must familiarize themselves with the concept of the Circle of Confusion (CoC). This is a technical term that defines the maximum acceptable blur for a single point of light to still be perceived as a sharp point by the human eye. In reality, a lens cannot project a perfect point; it projects a tiny circle. If this circle is small enough, our brain perceives it as a perfect point.

The standard CoC is typically defined in fractions of a millimeter and varies based on the camera’s sensor size. A smaller sensor (like those in phones or smaller mirrorless cameras) requires a smaller CoC to achieve the same appearance of sharpness as a larger sensor (like full-frame) viewed at the same distance. The size of the CoC is the actual technical limit that calculators use to determine the boundaries of the Depth of Field. Without this precise measure, the entire framework for Understanding Depth of Field in Photography would be purely subjective. The fact that different sensor sizes yield different DoF at the same settings is a primary reason why cinematographers and photographers carefully select their format.

The Three Pillars of Depth of Field Control

Controlling the Depth of Field is not accomplished by a single setting, but by the careful manipulation of three main factors that work in concert. A deep Understanding Depth of Field in Photography hinges on comprehending how these three elements—aperture, focal length, and distance—interact. Think of them as a triangle; changing one side inevitably affects the others.

1. Aperture (The Lens Opening)

The aperture is perhaps the most powerful and intuitive tool for controlling Depth of Field. It is the opening in the lens through which light passes, and its size is measured in f-stops (e.g., f/2.8, f/8, f/22).

Wide Aperture (Smaller f-number, e.g., f/1.4, f/2.8): This opens the lens up, letting in a lot of light, but it drastically narrows the Depth of Field, creating a very shallow focus zone. This is the classic look for portraits where the subject is sharp and the background is rendered as a pleasing, creamy blur (known as bokeh*). This is the key to Understanding Depth of Field in Photography for isolation.

- Narrow Aperture (Larger f-number, e.g., f/16, f/22): This closes the lens down, restricting light but widening the Depth of Field. This ensures that objects both near and far appear sharp. This is essential for landscape photographers who aim for maximum sharpness across the entire scene.

A common application in street photography is using a wide aperture (like f/4 or f/5.6) to get a moderately shallow Depth of Field, drawing attention to a single person while still providing context from the background. This balances subject isolation with narrative context. Truly mastering the art of Understanding Depth of Field in Photography begins with knowing your lens’s aperture limits.

2. Focal Length (The Lens Choice)

The focal length of your lens (measured in millimeters, e.g., 35mm, 85mm, 200mm) has a profound, though often indirect, effect on the Depth of Field. While technically, the focal length itself doesn’t change the DoF at the focus plane, its practical effect on the image is to dramatically magnify the background blur, making the Depth of Field appear much shallower.

- Longer Focal Lengths (Telephoto Lenses): A lens like a 200mm or 300mm will visually compress the scene, making the background seem closer and larger. Critically, it also magnifies the out-of-focus areas. This means a long lens appears to have a much shallower Depth of Field, even at a comparable f-stop, than a wide-angle lens. This visual compression and magnification are crucial elements in Understanding Depth of Field in Photography for subjects like sports or wildlife.

- Shorter Focal Lengths (Wide-Angle Lenses): A lens like a 16mm or 24mm has the opposite effect. It pushes the background away and makes the entire scene look expansive. This type of lens inherently has a very deep Depth of Field, making it easy to keep everything in focus from inches away to infinity.

When composing a stunning landscape, a photographer might opt for a 20mm lens stopped down to f/16. This combination creates an immense Depth of Field, a perfect application of Understanding Depth of Field in Photography for deep focus. Conversely, a portrait shooter aiming for an ethereal look will use an 85mm lens at f/1.8 to create an extremely shallow focus plane.

3. Focus Distance (The Proximity to Your Subject)

The distance between your camera and the subject you are focusing on is the final, and often most overlooked, factor in Understanding Depth of Field in Photography. This is a powerful, non-optical way to manipulate the focus plane.

- Closer Focusing: As you move the camera closer to your subject, the Depth of Field rapidly becomes shallower. This is why macro photography, where the focus distance is extremely short, results in a razor-thin plane of focus that is often measured in millimeters. The background is completely obliterated into a smooth wash of color.

- Farther Focusing: As you focus on a subject that is further away, the Depth of Field naturally becomes deeper. This is a crucial concept for street or travel photographers who often “zone focus” by setting their focus at a specific, mid-range distance, ensuring a wide zone of sharpness that allows them to quickly capture candid moments without constantly adjusting focus.

To demonstrate, consider shooting a small flower. If you focus from 3 feet away at f/4, you might have an inch or two of sharpness. If you then move the camera to only 6 inches away (maintaining f/4), your Depth of Field might shrink to just a fraction of an inch, making only the stamen sharp and the rest of the petals blurred. This extreme change based on distance underscores the importance of Understanding Depth of Field in Photography for detail work.

Creative Applications of Depth of Field

Understanding Depth of Field in Photography is not just a technical exercise; it’s a creative decision that defines the emotional and narrative quality of your image. How you choose to utilize the zone of focus is a direct representation of your artistic intention.

Shallow Depth of Field: Isolation and Emotion

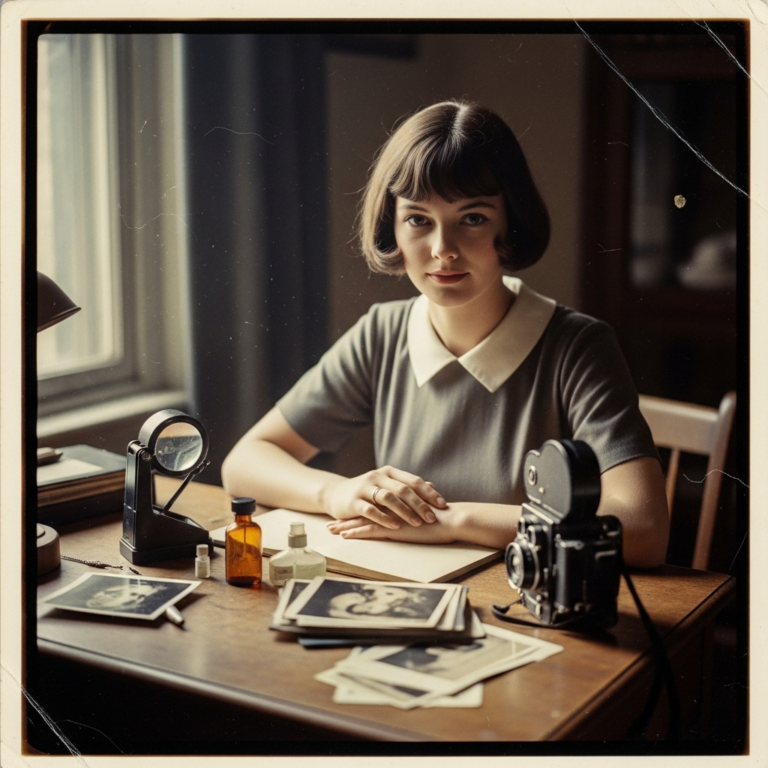

Shallow Depth of Field (sometimes called a narrow or thin plane of focus) is characterized by a sharp subject set against a significantly blurred background and foreground. This technique is overwhelmingly used to create a sense of intimacy and isolation.

Case Study: The Portrait Photographer’s Go-To.

A portrait photographer will almost always leverage a shallow Depth of Field. Their goal is to direct the viewer’s attention solely to the subject’s face and eyes. By using a fast lens (e.g., f/1.2 or f/1.8) and placing a distance between the subject and the background, they achieve that signature, professional look. The beautiful blur (bokeh) effectively removes distracting elements like messy power lines, busy crowds, or mismatched architecture, thereby strengthening the emotional connection between the viewer and the person in the photograph. This deliberate use of blur is essential to Understanding Depth of Field in Photography as a storytelling device. A razor-thin focus ensures the eyes—the windows to the soul—are critically sharp, while the ears or hair might already begin to soften.

Shallow DoF Use Cases:

- Portraiture: To make the subject pop against a soft backdrop.

- Macro Photography: To isolate tiny details like an insect’s eye or a water droplet.

- Food Photography: To focus sharply on a slice of cake or a garnish, making it look irresistible while the plate and table softly melt away.

The mastery of achieving the perfect shallow Depth of Field for a single rose is a true test of Understanding Depth of Field in Photography, requiring precise focus and a careful choice of aperture.

Deep Depth of Field: Context and Immersion

Deep Depth of Field (also called large or wide DoF) is the technique used when the photographer wants the maximum amount of the scene—from the nearest foreground element to the distant horizon—to be sharp. This method is predominantly used in genres where context and sweeping scale are important.

Case Study: The Grand Landscape.

Landscape photographers are the most frequent users of deep Depth of Field. Their primary objective is often to showcase the immense scale and detail of a scene, like a mountain range, a forest, or a city skyline. They achieve this by using a small aperture (f/11 to f/22) and often a wide-angle lens. Furthermore, they utilize the technique of hyperfocal distance. Hyperfocal distance is the closest point to the camera at which a lens can be focused while keeping objects at infinity acceptably sharp. By focusing at this specific calculated distance, the photographer maximizes the Depth of Field, ensuring the foreground elements (like rocks or flowers) and the distant mountains are all equally sharp. This complex calculation showcases a sophisticated Understanding Depth of Field in Photography and its technical utility.

Deep DoF Use Cases:

- Landscape Photography: To render maximum detail across the entire scene.

- Architectural Photography: To ensure all structural lines and details are crisp and clear.

- Documentary and Street Photography: To capture the context of a moment without worry about precise focus on a single subject.

For someone to truly achieve a stunning landscape where a foreground flower is as sharp as a mile-distant mountain, a solid foundation in Understanding Depth of Field in Photography is required.

Advanced Techniques: Beyond the Basics

To move from simply controlling the DoF to truly mastering it, one must explore several advanced techniques that leverage the principles discussed above. These methods allow for extreme control and are the hallmarks of professional-level work.

1. The Role of Hyperfocal Distance

As mentioned, hyperfocal distance is a specialized application of Understanding Depth of Field in Photography that is central to achieving extreme sharpness in deep focus work, particularly in landscape and night photography. While you can manually calculate it, modern photographers frequently use DoF calculator applications or online tools to find this exact distance.

The Practical Application:

Imagine a photographer standing on the edge of a cliff, aiming to photograph a majestic valley that stretches to the horizon.

- They set their camera to a narrow aperture, say f/16.

- They input their camera, lens, and f-stop into a DoF calculator.

- The calculator tells them the hyperfocal distance for those settings is 15 feet.

- The photographer manually focuses the lens precisely at the 15-foot mark.

The result is an image where everything from half the hyperfocal distance (7.5 feet) all the way to infinity is acceptably sharp. This maximizes the Depth of Field better than simply focusing on the furthest point and is a non-negotiable step for truly Understanding Depth of Field in Photography for grand scenes.

2. Focus Stacking: When DoF is Too Shallow

Even with a narrow aperture (like f/22), sometimes the Depth of Field is simply too thin to capture everything in sharp detail, especially in macro photography where the focus distance is minute. In these situations, especially for highly detailed product or extreme macro shots, photographers employ a technique called focus stacking.

The Focus Stacking Process:

- The photographer mounts the camera on a sturdy tripod.

- They take a series of identical photographs, changing the focus point slightly between each shot. The first shot might focus on the nearest part of the subject, the second a bit further back, and so on, until the entire subject is covered in a series of sharp planes.

- These images are then combined using specialized software. The software extracts only the sharpest parts of each image and merges them into a single, final photograph where the entire subject, even a tiny insect at high magnification, is perfectly sharp from front to back.

This technique is a creative workaround when the physical limitations of light and optics prevent a single shot from achieving the desired Depth of Field. It represents the pinnacle of technical skill in Understanding Depth of Field in Photography and its constraints.

3. Understanding the Visual Impact of “Bokeh”

While bokeh isn’t a factor determining the Depth of Field, it is the visual result of using a shallow DoF. Bokeh (a Japanese term meaning “blur” or “haze”) describes the aesthetic quality of the blur in the out-of-focus areas. It’s not about how blurry the background is, but what the blur looks like.

- Good Bokeh: Often described as creamy, smooth, or buttery. It makes the transition from sharp focus to blur soft and pleasing, often resulting in circular or polygonal highlights in the background.

- Poor Bokeh: Can appear distracting, harsh, or nervous, with defined edges or an ugly, busy pattern.

The quality of the bokeh is determined primarily by the lens design—specifically, the number and shape of the aperture blades. Lenses with more rounded blades (like 9 or 11 blades) generally produce smoother, more circular bokeh, even when slightly stopped down. For portraiture, a lens that produces excellent bokeh is often prioritized over all other technical specifications, making it a critical aspect of Understanding Depth of Field in Photography for stylistic effect.

Practical Tips for Mastering Your Depth of Field

Moving from theoretical Understanding Depth of Field in Photography to practical application requires experimentation and a few key strategies. The goal is to make the manipulation of the focus plane instinctive.

1. Shoot in Aperture Priority Mode (Av/A)

For beginners aiming to control DoF, shooting in Aperture Priority mode is highly recommended. In this mode, you select the aperture (f-stop), and the camera automatically selects the shutter speed to ensure a correct exposure. This isolates the most important variable in Depth of Field control, allowing you to focus on the creative impact of your f-stop choice. When you want a shallow Depth of Field, dial in f/2.8; when you need a deep Depth of Field, select f/16.

2. Practice with Primes

Prime lenses—lenses with a fixed focal length (e.g., 50mm, 85mm)—are often faster (meaning they have wider maximum apertures like f/1.4 or f/1.8) and sharper than zoom lenses. Working with a fast prime lens forces you to use the widest apertures, making the challenges of shallow Depth of Field immediately apparent. The experience of consistently nailing focus at f/1.4 is invaluable for truly advanced Understanding Depth of Field in Photography. Furthermore, prime lenses often deliver the highest quality bokeh, enhancing the creative impact of shallow DoF.

3. The Power of DoF Calculators

While physical distance scales on lenses are often too small or inaccurate to rely upon, digital Depth of Field calculators (available as apps for smartphones) are an essential tool for serious photographers. These tools are particularly useful for:

- Hyperfocal Distance Calculation: As discussed, for landscape work.

- Pre-visualization: Determining exactly what aperture you need to keep a subject at 10 feet and a background object at 20 feet both in focus.

- Learning the Variables: By changing the aperture, focal length, or focus distance in the app, you immediately see how the DoF changes, reinforcing your Understanding Depth of Field in Photography on a scientific level.

4. Distance is Your Closest Friend

Remember that moving physically closer to your subject has a far more dramatic effect on Depth of Field than a minor change in aperture. If you are shooting at f/8 and the background is not blurry enough, your first step should be to move closer to your subject, not simply stop down to f/5.6. This is a crucial practical tip for Understanding Depth of Field in Photography that separates the casual shooter from the intentional artist. In the same vein, to deepen your DoF, physically step back from your subject.

Common Mistakes in Understanding Depth of Field in Photography

Even experienced photographers sometimes make errors in the application of Depth of Field. Recognizing these common pitfalls can fast-track your journey to mastery.

Mistake 1: Not Considering Sensor Size

A major blind spot in Understanding Depth of Field in Photography comes from not accounting for the camera’s sensor size. A common scenario is someone moving from a full-frame camera to a cropped sensor (like APS-C) or vice-versa.

The Issue: A 50mm lens shot at f/4 on a full-frame camera will produce a shallower* Depth of Field than a 50mm lens shot at f/4 on a cropped sensor camera. This is because the cropped sensor effectively ‘crops’ the image circle, and by necessity uses a smaller Circle of Confusion to define ‘acceptable sharpness’.

The Solution: Always consider the crop factor. A 35mm lens on a 1.5x crop sensor acts like a 52.5mm lens (35 x 1.5) in terms of angle of view, but its Depth of Field will still be deeper* than a true 50mm lens on a full-frame body at the same aperture. This relationship is paramount for an accurate Understanding Depth of Field in Photography across different gear.

Mistake 2: Focusing on the Wrong Spot in the Portrait

When using a very shallow Depth of Field (e.g., f/1.4), the focus plane is paper-thin. A common mistake is focusing on the nose or the eyelashes instead of the eyes themselves.

- The Issue: If the camera focuses 1cm in front of the subject’s eyes, the eyes might be slightly soft, while the ears or the back of the head are already melting into the blur. The viewer’s eye is instantly drawn to the sharpest point, and if that point is not the subject’s eye, the image feels “off.”

- The Solution: Use your camera’s single-point focus mode, and ensure that the focus point is placed precisely over the eye closest to the camera. This level of precision is the difference between a good portrait and a great one, requiring complete Understanding Depth of Field in Photography and focus accuracy.

Mistake 3: Over-Stopping the Lens in Landscapes

A common assumption is that the smaller the aperture, the better the landscape. So, a photographer might stop their lens down all the way to f/22.

The Issue: While f/22 creates an immense Depth of Field, it often introduces a phenomenon called diffraction. Diffraction is an optical effect where light passing through a very tiny aperture opening scatters, causing a noticeable loss of overall sharpness* across the entire image. This counteracts the benefit of the deep focus.

- The Solution: The sharpest aperture for most lenses is usually around f/8 to f/11. For deep Depth of Field, a landscape photographer should rarely go past f/16. The most proficient photographers in Understanding Depth of Field in Photography know to prioritize sharpness and use the hyperfocal distance at f/11 or f/13 instead of sacrificing overall quality at f/22.

Conclusion: The Mastery of Focus and Blur

Understanding Depth of Field in Photography is the gateway to intentional, artistic image creation. It is the language of focus and blur, a dialect spoken by every powerful photograph. The technical foundation lies in the interplay of the three key factors: the size of the aperture you choose, the focal length of your lens, and the distance at which you set your focus.

The true master of Understanding Depth of Field in Photography knows that the goal is not to have an image that is sharp everywhere, nor one that is blurry everywhere, but one that is sharp precisely where the artist intends. Whether you are isolating a powerful expression with a super-shallow focus plane, or capturing the majestic sweep of a mountain vista with a deep focus, the control over Depth of Field is what empowers your storytelling. Continually practicing the manipulation of these variables—testing different apertures, distances, and lenses—will transform your skill set. Ultimately, full Understanding Depth of Field in Photography allows you to guide the viewer’s eye with purpose, dictating the narrative and the emotional tenor of every single image you create.

FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

How does Depth of Field relate to the sensor size of my camera?

Depth of Field is directly related to sensor size because of the concept of the Circle of Confusion. Smaller sensors (like those in APS-C or Micro Four Thirds cameras) require a smaller Circle of Confusion to render an image as acceptably sharp. This smaller CoC means that, all other settings being equal (aperture and focal length), smaller sensors will inherently produce a deeper Depth of Field than larger sensors (like full-frame). Therefore, achieving a shallow focus effect (like bokeh) is easier and more pronounced on cameras with larger sensors. This technical reality is essential for an accurate Understanding Depth of Field in Photography.

What is the ‘sweet spot’ aperture for maximum sharpness?

The “sweet spot” is the aperture setting that provides the best balance of sharpness across the entire image, maximizing lens resolution while minimizing the negative effects of optical aberrations and diffraction. For the vast majority of lenses, this sweet spot for maximum sharpness is usually located two to three stops down from the lens’s widest aperture. For example, if your lens opens to f/2.8, the sharpest point is likely to be around f/5.6 or f/8. Photographers aiming for the best technical quality must achieve this nuanced Understanding Depth of Field in Photography and its relationship with lens physics.

What is the fastest way to get a very shallow Depth of Field?

The absolute fastest way to achieve an extremely shallow Depth of Field is to employ all three primary factors simultaneously: use the widest possible aperture (e.g., f/1.2 or f/1.8), use a long focal length (e.g., 85mm or 200mm), and move the camera as close to the subject as possible. The combination of a wide-open lens and close focus distance is what creates the most dramatic, paper-thin plane of focus, a true showcase of advanced Understanding Depth of Field in Photography for isolation.

Why is the out-of-focus area often called “bokeh”?

The term “bokeh” is a transliteration of a Japanese word meaning “blur,” “haze,” or “fuzz.” In photography, it doesn’t refer to the amount of blur, but rather to the quality or aesthetic of the out-of-focus areas of a photograph. Lenses are specifically judged on whether they produce pleasing (smooth, creamy) or distracting (harsh, nervous) bokeh. An advanced Understanding Depth of Field in Photography always includes a critical evaluation of the resulting bokeh quality.